To journey into the heart of outback New South Wales is to find the Australia depicted in movies; a moon-like landscape, home to outback chancers and ancient stories. Come with us on this outback road trip like no other.

Rissole the emu is motionless, looking me dead in the eye. At this close range, it’s clear she’s either sizing me up for fighting, feeding or mating, and the cerulean shade painting her neck in a dirty watercolour makes me surmise she’s showing her breeding colours. Rissole, I’m thinking, is ready for love.

She punctuates the silence with the oddest sound I’ve ever heard issued from a living thing – a kind of booming poonk from the depths of her throat that makes me alert, slightly alarmed and not at all able to take her seriously.

Leaving Rissole to send her poonks into the air to be heard by bachelors up to two kilometres in each direction, I hear the exact same sound from an even less expected source. Eddy Harris is the resident artist at Warrawong on the Darling, here on the breezy billabong outside of Wilcannia in outback New South Wales, and his place as part of the Bakandji (river people) mob means he can not only recognise the emu’s call but can recreate it with a squat, decorated section of tree trunk that I mistook for a short didgeridoo.

He thumps it and it thumps back with a poonk. We’re indoors, alongside the hotel reception in the gallery colourfully filled with Eddy’s detailed, soulful art creations, and I hope the sound doesn’t escape to give Rissole the wrong idea.

As Eddy starts recounting quiet tales of the area, I feel like I have the wrong idea about Wilcannia. But I know what I see: once the country’s third busiest port, the stately architecture and wide streets hint at Wilcannia’s mercantile past. However, now those wide streets are entirely empty of humankind, the supermarket boarded up, and the Darling River stolen to a trickle by upstream farming concerns. Population 600, it is a question mark of a town, intriguing and worrying in equal measure, perched upon the precipice of a rich past and an unmaintainable present. I see a ghost town in the making.

But with Eddy’s help, I also see a country thick with tradition and story, for anyone willing and able to take the time to go for a walkabout. This countryside’s songlines have massive breaks in them, so the young people’s framework for traditional learning sits on shaky foundations, but Eddy and his elder contemporaries are repairing the bonds, restoring pride in country. They take them into the forest and teach them how to tell their story through art, to provide the catharsis that Eddy himself experiences with every single artwork.

“I get feelings out there, out in country," he confides, gesturing beyond the bird-swooped billabong. “Sometimes too many – I have to do something with them, to look after myself. So I make art." It’s all gazetted in paint: bird tracks in flood season, the landscape’s colour and the many dreamings that speak for the land.

Mine, all mine: White Cliffs

North of Wilcannia, the red earth turns a rocky white. The gibber plains (small rocks and pebbles) spelt the end for Burke and Wills’s camels, unable as they were to navigate the purplish shining stones surrounding the town of White Cliffs; but those who followed had dollar signs in their eyes. Ever since roo shooters stumbled across a precious white opal here, a tight community of dreamers has called this desolate town home, with an estimated two-thirds of the 100 or so residents living underground to escape the lunar-level extremes.

“I don’t know why I stayed," says resident Cree Marshall, among the white-washed tunnels of her unexpectedly luxurious underground home. “You either love it or you hate it here, but there’s just something about the land that’s so powerful. It just lets you be what you want to be." She welcomes visitors into her home for $10 a pop, and it’s worth it.

Her artistic streak is apparent in a giant angel on the wall, made from a sewing machine table and a box-worth of Thai leather belts; in emu eggs lined up, bleached from the sun to form a modish pattern; and in the mosaic floors, which somehow manage to follow the curving, labyrinthine walls. She and her handy-as-hell partner Lindsay White began to convert this erstwhile mine into a home about nine years ago. Its mining past means a few dead ends here and there, but it’s certainly one of a kind.

The Underground Motel in town offers a first-hand experience of living in the white tunnels under White Cliffs, with a long staircase to take you topside to drink in the slow desert sunset from atop the earthen motel mound – the ‘rooftop’, if you will. A swimming pool and underground bar complete the good-life vibe, but there’s no escaping the true nature of the town down the road the next morning.

The Blocks are the current major diggings being worked by ambitious miners looking for the Big Find; pits and mounds scar the surreal landscape like the burrows of a hundred giant meerkats. Overlooking it all is the entrance to the mine belonging to White Cliffs success story Graeme Dowton, whose sandy-haired charm hides either a steely will or a deadset addiction to the digging game – or both. Either way, visitors can explore his mine with him and even rummage through the opal chips on the ground, then see his famous white opal ‘pineapples’ back at his headquarters at Red Earth Opal .

These huge chunks of opal number less than 200 in the world and can fetch up to US$70,000 from collectors, which explains Graeme’s rather happy demeanour. Down in the mine, he waves his hand vaguely toward a small dead-end passage still being worked on. “This little section is worth about six or seven hundred thousand to me," he says in passing. This is a man who’s struck it rich in one of the toughest opal fields to work in the world, and there’s a genuine kick in bearing witness.

The veins of ancestors: Mutawintji National Park

Mutawintji National Park , further along from White Cliffs and a veritable oasis protected by both green-tinged hills and the determination of the local Aboriginal land council, shines a somewhat different light on mining.

In one Bakandji dreaming, my guide Mark Sutton tells me, the people were turned into veins of silver and lead by divine force, “which explains our unease with it all. It’s like disinterring our very ancestors. But we’ve had to put up with mining almost since white people came here."

It’s a privilege to walk the land here with Mark. The open, wave-like caves fringing the valley shelter some mind-blowing history, and they’re not for the casual visitor – you need to be brought here by an accredited local guide. The pay-off is rich: cave after swirling rock cave, acting as billboards to display the story of people who’ve passed by. Full armprints from elders, or simple handprints from the younger ones, just initiated. A somewhat cluelessly blue one from William Wright brings to mind the stories about him – that his refusal to meet Burke (as in, Burke and Wills) at the appointed location, due to non-payment, spelt ultimate disaster for the famous expedition and death for Burke and his men.

Up on a jagged, impressive hillside, all that modern history seems like ridiculous bickering. These carvings were tattooed into the shining, fragile rock face perhaps as early as 5000BC. An ancient, carved emu bends its head, forever surveying the cypress pine and mulga of the valley below, and the vertigo hits me, of not only our precarious perch on the hill but our much more precarious perch in the vastness of time. What a wonderful way to feel very, very small.

Lead and silver and feathers: Broken Hill

Two hours away is Broken Hill. It is metal and boots and a reputation for dust from the rampant mining that built the city, though the dust has settled, thanks to a bush regeneration zone ringing the district that has cleared the air. In bathrooms and on local TV, you’ll encounter reminders to mop the floors and wash your hands, to keep the lead dust from coming home each day. The transcontinental train line shines beside the giant slag heap; the grey heap, in turn, is a stone’s throw from the gay colour, in every sense of it, found within the Palace Hotel . The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert filmed here, and left an indelible trail of pink feathers behind it; gruff miners sink a few cold ones among sequins and frescoes, and it all somehow makes sense in a place like Broken Hill.

Out of town, a small mob of emus splashing in a precious puddle guards the Living Desert and Sculptures park; I still go out of my mind with excitement at seeing emus in the wild, always a dream of mine before this trip. The sculpture park makes sense in Broken Hill too: the majestic curves of the artworks crowning the hill herald a deep love of creativity that is as much a part of the city as the red earth and sparse, flower-dotted scrub stretching across the plains beyond the park’s lookout is.

One of the emus keeps pace with the 4WD bus as we head away, as if to coax us into staying a little longer, but we’re picking up speed on a road that seems to have as many dips as a good-sized cocktail party. Because Queen Elizabeth herself graced these parts on her 1954 tour of Australia, the road out to the famous old mining ghost town of Silverton was hurriedly paved – and it seems like they missed a few spots. The dusty roads of Silverton are now mostly walked by itinerant donkeys and mowed down by the fat tyres of Mad Max 2 fans who’ve come to see the locations filmed back in 1981. So no one’s complaining.

Head out from Broken Hill on a different road, though, and gigantic water-supply pipes trace a straight line to a wonderland of green and blue, a landscape transformed in a matter of moments: the Menindee Lakes. Holding more than three times Sydney Harbour at their peak, the massive waterways wind their way through impossibly green grass with nary a blade of it pressed by a footprint; the main population is in the trees and the sky, with thousands of birds insouciantly watching our progress by boat. Squadrons of pelicans lazily take wing, Nankeen herons vainly pose and Jesus Christ birds seemingly run across the water as they take off – hence the name.

And even here, the emus are resident. Three of them, distant but clear in this crystalline environment, narrow their eyes at me and take off running along the bank, outpacing the boat, and the thrill in seeing them hasn’t worn off. Much like the hillside carving back at Mutawintji, they’re more a part of this place than I’ll ever be, but I’m good with that. It won’t stop me coming back. Not in a million years.

The details: Outback road trip (New South Wales)

Getting there: You can fly to Broken Hill with Rex from Sydney, Melbourne or Adelaide, take a train from Sydney or travel on the iconic Indian Pacific from Sydney or Adelaide if you’d like to do it in style.

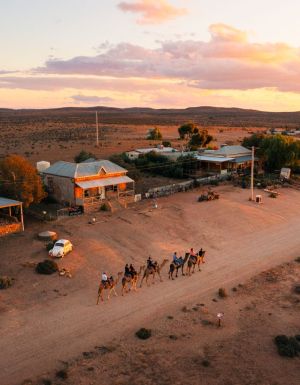

Playing there: Visit these places with Tri State Safaris on its 3 Day Outback Exposure tour, from $1380 per person twin share. It includes stays at the White Cliffs Underground Motel, Warrawong on the Darling and other local accommodation, all owned by Out of the Ordinary Outback.