East Arnhem Land is a stunning wilderness bound together by pockets of rich Yolngu culture, well worth a journey, if only to see thriving indigenous communities in action.

Here are five things you’ll want to know before the big journey, writes Steve Madgwick.

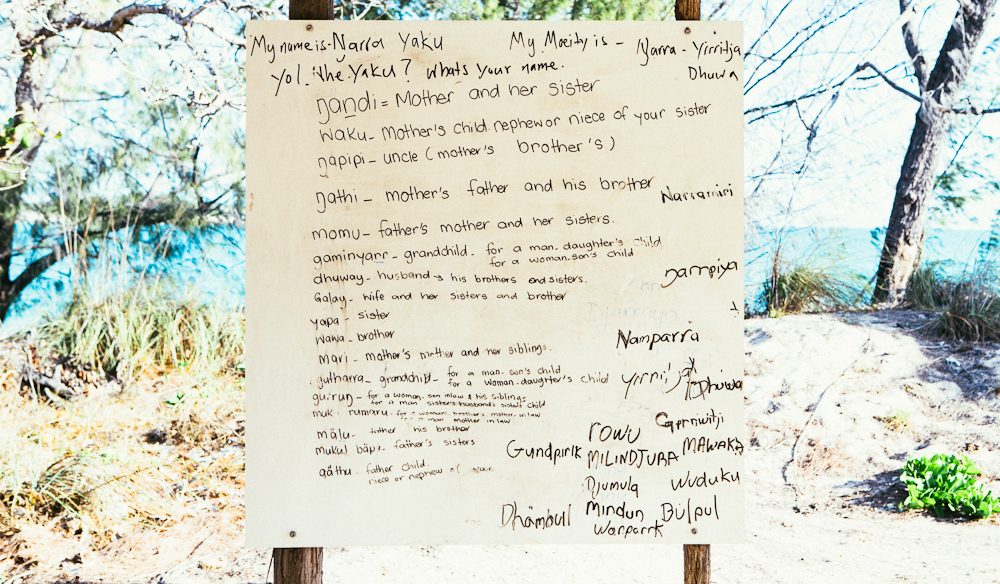

1. Think your family is complicated? The Yolngu kinship system…

In the intricate Yolngu kinship system, each person is one of two classes known as a moiety – Dhuwa or Yirritja. The designation is regardless of clan and derives from the father’s side. Traditionally, everyone must marry outside their own moiety.

Next in the ID tree, everyone also has ‘clan’ and ‘skin’ names, which can make for intensely complex relationships (for an outsider to understand) between siblings. In some instances, certain brothers and sisters are not allowed to speak to each other directly.

The overall objective is for the two moieties to exist in harmony, like ‘Yothu Yindi’, mother and child. Confused? So are we.

Unless you live within this culture it could take years to grasp the nuances of this complex system.

2. Bawaka: the most beautiful beach in Australia?

East Arnhem Land has seriously raw natural beauty, but Bawaka, home to the Burarrawanga family, stands tall even in such auspicious company. A couple of very sandy hours’ drive south from Nhulunbuy brings you to the small settlement on palm-tree-strewn, pearl-white beaches.

Bawaka also hosts a variety of cross-cultural activities such as the two-day Gay’wu Women’s Program. You may also want to keep an eye out for resident coconut-loving crocodile ‘Nike’ at this eastern Port Bradshaw homeland.

The reptile was reportedly named in honour of Cathy Freeman’s Olympic heroics and can be seen sunbathing on the sand here.

3. A very different constitution

Buku-Larrnggay Mulka may be the best indigenous art centre in the country, thanks to its powerful variety of Yolngu bark paintings, weavings and jewellery. It also houses modern artefacts critical to Yolngu law and spirituality, headed by the Yirrkala Church Panels.

The two four-metre-tall painted boards (one for each moiety, with all clans represented) are akin to a constitution.

4. Garma: the must-go festival

Everything about modern Yolngu culture is embodied in the annual Garma Festival, held in August (reasonably easy to get to by Arnhem Land standards, if you fly into Nhulunbuy).

It’s arguably Australia’s most important indigenous festival with ceremonies, celebrations and debates.

5. The ethics of dining on dugongs and turtle eggs

Inevitably you will be faced with difficult decisions in East Arnhem Land about eating animals not usually found on your plate.

Hunting and eating turtles and dugongs, for example, is integral to Yolngu culture, a controversial and hard-fought for right.

Waka Mununggurr was protecting his own part of Blue Mud Bay long before Anglo-Australian law allowed him to do so. “I used to chase a lot of Vietnamese, Filipino and Cambodians around those bays. I used to tell them not to be there."

A legal fight then began against commercial fishermen, which ended up in a five-year court battle. This effectively gave the Yolngu sea rights to the area.