Join the Yolngu nation in the NT’s remote North East Arnhem Land to feel the heartbeat of the country at its most important cultural event, Garma.

Where it all began

Australians pride themselves on being an intrepid mob. As travellers we hanker for republics and cultures afar, places with ‘real’ history and cultures that corroborate our wisdom, our worldliness, our wokeness.

Yet, inscrutably, most of us fail to appreciate that one of the oldest and most complex cultures on Earth is right under our noses. So why is it that so few of us have sat down in the red dirt of North East Arnhem Land, home to the robust Yolngu nation, and arguably the most significant cultural event in Australia?

Perhaps many non-Indigenous Australians genuinely don’t know how and where to begin to engage with First Nations culture. Perhaps, subconsciously, the cultural divide feels too titanic, the multifaceted historical baggage and societal inequities too hard to reconcile.

At a great cultural crossroads of history, when our national identity is as fluid as ever, perhaps Garma has the ability to collapse all these ‘perhaps’. The stirring four-day festival is an unabridged cultural bridge, anathema to the terra-nullius-tainted version of ‘Australian history’.

“Too often in Australia we talk about this Indigenous problem or that Indigenous problem," says author Richard Flanagan. “We never talk about the Indigenous gift, the great gift of knowledge, of understanding."

This gift softly, subtly and slowly unfolds as you walk into Gulkula festival ground because the Yolngu nation is one of the most dynamic of all of Australia’s original storytellers.

“When you come here, it’s still alive – very much alive," says long-time Garma ambassador Jack Thompson, fresh from leading his morning tai chi class.

Late last night he recited bush poetry by the campfire. “You are surrounded by people speaking their language, doing their ceremony. The whole country must have been like this. That’s why Garma recharges my batteries."

Why is it that so few of us have sat down in the red dirt of North East Arnhem Land, home to the robust Yolngu nation, and arguably the most significant cultural event in Australia?

Some might say it’s disingenuous to introduce an Indigenous festival through the voices of (albeit compassionate) white Australians. But unlike generations before them, they are not trying to ‘white mansplain’ Indigenous culture. They are simply imploring you to listen to the stories of Yolngu because doing so has incalculably changed their lives for the better.

The Welcome

You can leave your passport in the shoebox under the bed, but in countless other ways North East Arnhem Land feels like a sovereign entity. Aided by relative isolation from Australia’s all-consuming metropolises, the Yolngu’s 50-millennia-old manikay (song) and miny’tji (art) exude poise and confidence: an unwavering cultural backbone that launched far-reaching land- and sea-rights movements.

“We have maintained, protected and enhanced our world view since the first outsiders appeared in the 1930s and tried to kill us and take our land," says traditional owner Dr Galarrwuy Yunupingu, senior leader of the Gumatj clan. “Hear our words, watch our ceremonies, place your feet in the sand with us and enjoy our hospitality. We will exchange ideas, make friendships, learn from each other. Go feed your brain!"

Garma’s opening ceremony is as inclusive as any you will see on this continent: dark faces, darker faces, Islander faces, and white faces beading under hats and sunscreen, perch together on plastic chairs facing unfettered monsoon forest. Tieless, unbuttoned politicians squirm uneasily, aware that people on the Dhupuma Plateau won’t stomach any vacuous, business-as-usual rhetoric.

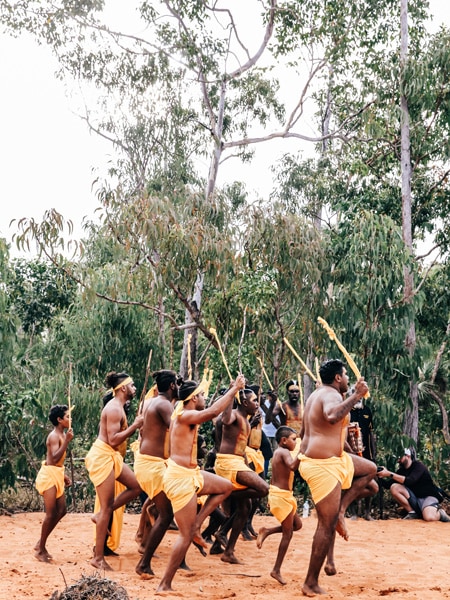

Bilma (clap sticks) pulse from the bush. Heads swivel, eyes chase the sound. Generations of Gumatj clan men stealth from the trees like wary sentinels, ceremonially led by the Minister for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt, draped in a ritual roo pelt. Intense yellow and red paint covers their torsos like divine armour. Eyes fall on a bubble-cheeked youngster at their feet, at one with their totems in dance, while stringybarks sough mystically.

At the lectern, ubiquitous Jack’s speech is received well as always. Long ago, he was brought into the Yolngu fold. They call him Gulkula now, after this sacred place. Even the magpie geese hush when Dr Yunupingu informs the gathered that he will throw Australia’s constitution into the nearby Arafura Sea if his people are not recognised in the document. And with that, Garma is officially open.

The Voice

Eloquent, tough-talking hard-act-to-follow follows eloquent, tough-talking hard-act-to-follow at Garma’s Key Forum. Speech roams free, discussions dive unapologetically deep into the irrefutable inequities between white and black Australians, from educational outcome disparities to reprehensible gulfs in life expectancy.

This is not the place for either trolls or ‘poor us’ navel gazing with some of Australia’s deadliest minds on hand to fact check ignorance and fly-kick generalisations. Professor Marcia Langton pays homage to the profound Indigenous knowledge systems taught to her by Yolngu elders that will be invaluable in the nation’s curriculum. Noel Pearson sermons his trademark intricate metaphors, championing “radical hope" and “unfounded opposition".

The word Makarrata (a Yolngu word that synthesises treaty, peace-making and justice) flows from the mouths of key speakers naturally, then ripples organically into the festival lexicon. The Uluru Statement from the Heart, that poetic path forward for Indigenous constitutional recognition, binds disparate subjects together into a singular hope-filled trajectory.

You can leave your passport in the shoebox under the bed, but in countless other ways North East Arnhem Land feels like a sovereign entity.

Restless minds rumble as loudly as their hosts’ bellies in the notoriously long communal lunch buffet queue. Apart from being a killer spot for celeb-spotting, the sluggish, snaking line is dotted with impromptu mini-forums where well-qualified strangers debate serious stuff with smiles on their faces. One old fella tells me that Uluru shouldn’t be closed to those who approach it with an open heart. Not a popular idea here, but the people listen to such diverse thoughts without ‘cancelling’ him – then counter with a learned rebuttal.

The Heart

Back in 1999, Garma began more or less as a ‘backyard barbecue’. If you ignore the relative formalities of the Key Forum, it is still very much a bush festival for and by the local community as it is a platform for parachuting powerbrokers. Expect peak-time shower queues, sporadic power outages rescued by snarling generators, and a long wait at the merch stall, which is denuded voraciously (unless you’re XXXL).

The Bunggul is Garma’s geographical and metaphorical thumping heart, a sandy circle where the sacred becomes normal, and the normal sacred. A place to hang out, connect and reflect. The Gumatj spiritedly welcome other clans to perform (and visitors to join in) on their hallowed ground.

“I just called the people from the Gulf [Groote Eylandt] again – they’ll be right over," explains the MC, shrill speaker feedback sending community canines into tornadoes. A fourth hurry-up draws a posse of vivid red and white across the oval. Traditional dress is accessorised with sunnies, trucker caps and t-shirts with off-country allegiances.

A string of stage-front yidaki (didgeridoo) players sparks the Morning Star dance to life. Clap sticks crack an enduring atavistic heartbeat. Two aunties in tropical-strength dresses that are stories in themselves sway on the outer edges, bare feet rooted into the sand, while the men dance their stories. The MC tries to decode the hyper-dynamic action for the thousands of out-of-towners.

The Gumatj dancers hover in next, branches and water bottles in hand; smokes in the mouths of a couple. The women’s yellow skirts with sharp red flames licking high are a sartorial highlight. The energetic ‘quest for the sugarbag honey’ explodes; fast feet slice through and spray sand. Meanwhile, a joyful woman on the Bunggul’s grassy periphery pulls mad doughnuts in her motorised wheelchair.

The Wisdom

“The cycle of a day can be very different when experienced through the Garma lens," says event director Denise Bowden. “You are on Yolngu land, living with Yolngu people, under the authority of Yolngu elders."

Yes, understanding Arnhem Land’s cultural nuances can be a challenge, but the Yolngu struggle to comprehend outsider culture equally. Today and for much of his life, Djalu Gurruwiwi has sought to bridge the new and the old worlds, at least for those willing to cast aside their Western World lens (and baggage).

The sage elder sits in a shady camp chair, a mop of a dog curled at his feet. His storm of grey hair, blue iridium sunglasses, striped polo shirt and black Skechers strip 40 years off the 89 year old. Thought bubbles sporadically burst from his mouth in Yolngu Matha (Arnhem Land’s lingua franca) through a dinky PA system that is more trouble than it’s worth. His hands swoop like hunting falcons to illustrate what his ancestors have passed on.

Djalu believes that the sound of his yidaki has the power to heal, that it transcends cultures and can connect all people to this earth. His daughter Zelda Gurruwiwi translates into English. She eagerly injects her own experience and self into the narrative.

“When I was a little girl, the ancestors, old tribal people, used to bring their cultural sacred therapy to ceremonies," she says. “These days, it’s a bit lacking. That’s why my dad stands here – bringing people to one unity, one nation.

“This yidaki is bringing culture and people together, leading to a doorway to our culture, our ceremonial ground. People in the Western World, it’s time for you to come into the spiritual world. Some people call me crazy. I am not crazy. They are crazy. They are not looking at the gateway to nature. My dad, he’s the last knowledge. Old people will take that knowledge back to the ground."

Djalu blows into the trunk. The soft, profound timbre immediately usurps the festival’s clamour. Jack Thompson wanders by, plops himself in a camp chair opposite. Djalu offers him the yidaki’s end. Jack delicately shuts his eyes, receives the vibrations willingly.

The Family

“See all the people here; we’re all related," says Brenda ‘Mutha’Muthamuluwuy, gesturing at the various clans camping in the bush. She seeks signs of understanding from those congregated under the bough shelter, rewards us with earnest smiles and a motherly “manymak" (good) before moving on. She knows that the Yolngu kinship system is a foreign matrix to those from nuclear families.

“In your world, you are related only in immediate family, right?" she asks. “Well, ours is different, it goes down and it spreads. For example, my mother’s sister’s children are also my brothers and sisters from another mother. We can still call each other sister even if we have different parents. Some of our grandkids’ children can also be sister and brother."

She references a photocopied schema of the gurrutu, which shows a multi-directional cascade outward from ‘you’, featuring 23 relationship titles. She introduces the concepts of ‘skin names’ and the two ‘moieties’, dhuwa and yirritjia (each Yolngu must marry into the opposite moiety). Then comes Mutha’s mic-drop moment.

“It’s not just a person either," she says. “The land, sea and nature – trees, birds, snakes, fish – are related to us in kinship, too. The whale is my grandmother’s totem, so I am related as a granddaughter to the whale in Dreaming."

The Expression

Northern Australia’s darkest night cannot stop the miny’tji (art). By torchlight, at 10.30pm, second-year art student Dylan Mooney dabs his final touches to a portrait for the ‘Great Wall of Garma’ (aka Art Build). The day before, Archibald Prize-winning artist Ben Quilty tentatively swiped a final stroke on his contribution to the communal mural.

“[Being up here] is the biggest imposter syndrome that I’ve ever felt," says Ben. “[I’ve] had the honour of meeting some of my greatestidols, like Ai Weiwei, but the best painters in the world are living in Australia’s remote communities. I don’t say that lightly."

Behind the mural, down a bush avenue, single paintings hang from Gapan Gallery’s lofty gums. Stalls stocking stunning ‘fibre art’ from community art centres such as Bula’bula at Ramingining, 400 kilometres west, encircle the open-air cultural microcosm.

Intricate, naturally dyed pandanus leaf baskets, mats and dilly bags from Arnhem Land’s women master-weavers are in high demand. The more experienced aunties’ masterpieces justifiably command top dollar. They take lifetimes of skill and time.

One of Muluymuluy Wirrpanda’s dense black, white and grey linocuts hangs from a whitewashed display tree. It is a privileged close-up of Yolngu existence, both the story of a day in her life and of the culture that has nourished her. She describes the piece sparingly, through an interpreter, a few words of English mixed in, as if the ‘bulwatja’ story is self-evident. How long did it take?

“Not too long, just doing the outline mainly," she says. Our eyes never meet. “The bulwatja is a billabong plant. When we went hunting, we’d always get bush food, too. I get to eat it and make art from it."

in front of her artwork at the Gapan Gallery. (Credit: Elise Hassey)

Traditional or modern style, I ask? She doesn’t answer. Probably because it is neither and both. It just is and has always been so.

The Exhale

Final-day Garma is a wholly different animal to its frenetic first few days. Politicians have returned to their far-away constituencies; corporate-sponsor bigwigs have fled back for their high-rise Monday-morning meetings. Those who remain magnetically contract into the Bunggul.

Lithe-legged kids kick footies back and forth with grinning cops and giggling ambulance officers. The dancing rolls on unstoppably: less formal, more freestyle, the line between crowd and performers hazy. “Copy what everyone else is doing or just do your own thing," says the MC. Thongs on thighs make for modern pliable clap sticks. Each song is full-stopped with a booming, community-wide “Yo! " (yes).’

Dan Sultan summons a storm on stage; he admits he’s been nervous performing at his first Garma, then shares a few private demons. “All the way from Stone Country" Black Rock Band and Southeast Desert Metal momentarily spike people out of their descent into end-of-festival chill. The choral notes of all-female Spinifex Gum’s Dream Baby Dream cover draw people to their weary feet for one last time in the darkness.

One by one, clan flags are lowered. “You can stay if you want or you can go," croaks the MC. “I just hope you’ve spread the good karma at Garma."

The doors of 2650 guest tents flap empty in the dry-season morning breeze. Tomorrow the snakes and water buffalo that volunteers shooed away will slither and clomp back to claim their piece of Gulkula until next year.

Physically spent but spiritually stirred first-timers reluctantly cram into airport-bound mini-buses. Minds whirl with cultural epiphanies and inequities reimagined. They are like human message sticks, keen to spread what they’ve heard, seen and felt.

“Every Australian should come; every Australian schoolchild should have it as part of their curriculum," says Jack Thompson. “Otherwise, for many, your only experience of Aboriginal people is as the fringe-dwellers; people in the cities disinherited from their culture."

Generations of misinformation and ignorance don’t stand a chance when you come face to face with the people of this strong, alive country at this great Indigenous festival. Sorry, make that at this great Australian festival.

A traveller’s checklist

After being cancelled in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the annual Garma festival, run by the Yothu Yindi Foundation, is due to take place this year from 30 July to 2 August.

Getting there

Airnorth and Qantas have flights to Nhulunbuy; transfers from Gove Airport to the festival site are included in the ticket price.

Staying there

The ticket to Garma includes camping accommodation in an assembled tent with sleeping bag and air mattress, all meals, and basic tea and coffee facilities.

Exploring there

A Garma ticket acts as a permit to enter Aboriginal land, however, if you wish to visit other Arnhem Land communities outside of the festival proceedings, permits are required.