Roaming with buffalo, cruising with crocs and gliding with some 280 bird species that live here in this watery world: a safari through Australia’s Top End wilderness is an unforgettable immersion.

Windows down, the warm air is sweet and dank with flowering paperbarks. It’s the start of the Dry and Sab’s tyres slice through the submerged road that is still blended into the adjacent billabong.

We’re not in Sydney anymore, where water is defined by the lines of the harbour foreshore. And we’re not in Darwin either, where the tropical waters of the Arafura Sea lie flat at its beaches, and simulated waves at the waterfront slosh holidaymakers around like rubber ducks.

We’re in the watery world of Kakadu: Australia’s largest terrestrial national park, heritage listed for both its cultural and natural significance, and just three hours north of the Northern Territory’s capital.

One hundred and forty million years ago Kakadu was under a shallow sea and the dramatic escarpments of its so-called stone country were sea cliffs; today, wetlands cover more than one third of the park’s 20,000 square kilometres. A quarter of all Australia’s freshwater fish species live here, along with a third of its bird species and one-tenth of the Territory’s saltwater crocodiles.

And while we can navigate it with human ingenuity – driving through rivers and propelling ourselves across floodplains – we’re really just the interlopers here: awkward and awestruck while all animal life glides and swoops and swims around us in rhythm with the ecosystem.

Cruising the Yellow Water Billabong

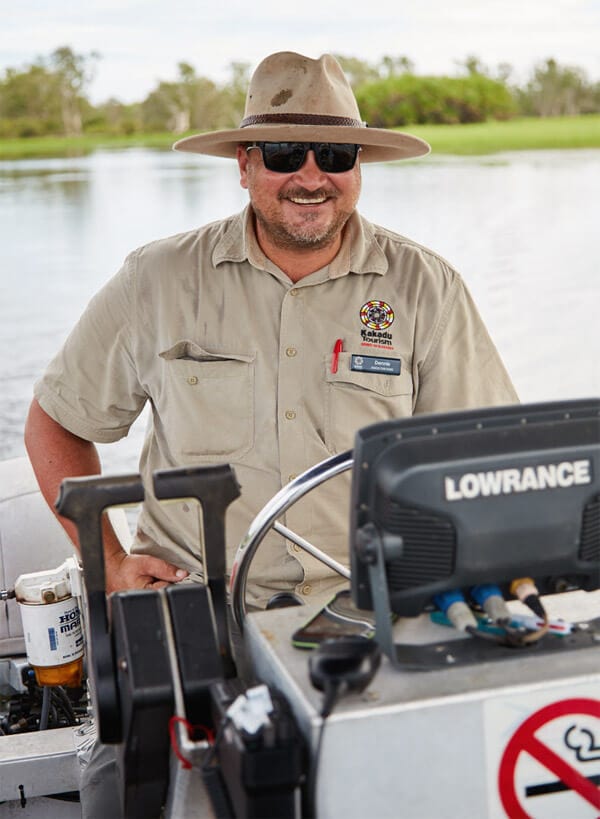

The feeling first strikes me a few minutes into a cruise on Yellow Water Billabong. Our guide Dennis kills the boat’s motor and the water stills to a glassy film while the whooping and whistling of birds fills the air.

This pristine 10-square-kilometre environment is both impossibly tranquil and teeming with life. Sea eagles fish and jabirus forage; jacanas – or Jesus birds – appear to walk on water; azure kingfishers dazzle in flashes of blue and orange.

We edge toward the fringes of the billabong, where a lone water buffalo sizes us up from the floodplain, before we come across a telltale outline in the mud of the shallows. Silent, still and so uncannily real that, conversely, it looks unreal, the saltwater crocodile is completely at home in its natural habitat.

Later, we trail a few-metres-long croc – or snapping handbag, as it’s called round here – for a captivating couple of minutes; it’s so close I could almost touch it with an ill-advised outstretched arm. It’s unperturbed by us, Dennis says; the resident crocs here are used to these strange tin cans full of gawkers. The pattern of its scales and swish of its tail leave hypnotic tracks in the water. And then, just like that, it slips away.

A four-day tour with Lords Safaris

I’m on safari in the Top End: a four-day toe-dip into the wildernesses of Kakadu, Arnhem Land and the Mary River floodplains with Lords Safaris , a founding member of Australian Wildlife Journeys.

My guide is Sab Lord himself, a legend in these parts, raised right here on a Kakadu buffalo and crocodile hunting station. That he brings to each tour a deep knowledge of local wildlife, terrain and culture acquired over a lifetime is just one of the reasons he’s among Australia’s most in-demand private tour guides; he’s a true larger-than-life outback character too.

With 27 years’ guiding under his belt and the requisite battered old Akubra on his head, he slings Aussie-isms around like “mad as a meat-axe" and brings Kakadu to life in unexpected ways with tales of the old days. We travel in a luxury 4WD and tow a trailer Sab customised to accommodate everything a journey like this involves; it’s done a million kilometres, traverses red dirt roads and rivers no sweat, and doubles as a picnic table come lunchtime.

Day one: Darwin to Lords Safaris’ private camp

Setting off early from Darwin, we pack a lot into our first day. An experience with Pudakul Aboriginal Cultural Tours leaves me with an impression of traditional life on the wetlands and at Fogg Dam I learn about the grand plans once hatched to turn northern Australia into a rice-growing hub; today the reserve is a haven for wading birds.

We eat lunch and spot dragonflies at Leaning Tree Lagoon, and later cruise Yellow Water. By the time we arrive at Lords Safaris’ private camp in the evening, I already feel at home in this habitat too. In a clearing between the ironwoods and stringybarks, and under the watch of visiting kookaburras, Sab cooks dinner over the campfire.

His entertaining stories of celebrities he’s taken on tour – a Meryl here and a royal there, and some, like Nicolas Cage, he’s still mates with today – are only surpassed by his wild tales of Africa, a home away from home he revisits each year that inspired him to develop the concept of an Australian safari.

Bedtime is in one of the camp’s comfortable bush-side cabins; when I wake the next day, red morning light is filtering through the trees and breakfast is already sizzling. We hit the road for Gunlom Falls.

Day two: Gunlom Falls

It’s a short, steep climb up the height of the waterfall to reach one of Kakadu’s most iconic spots: a smaller waterfall that pours into a natural infinity pool, Gunlom Plunge Pool, which in turn gives way to spectacular views of the park’s far reaches.

For a few minutes after we arrive, we have the blissful good fortune of the place to ourselves and the illusion of it being the world’s best-kept secret. I slip in and swim to the water’s rocky edge; a feeling of privilege washes over me as I linger here looking out over the southern hills and ridges. Sab, meanwhile, dozes on a rock with his hat cocked over his face; it’s all in a day’s work when places like this are in your backyard.

In 1957, Sab’s father John Lord flipped a coin. Stay in Australia or start a new life in Argentina? Chance and a pioneering spirit sent his parents north to the Top End in a Bedford truck; they cut a path through the bush as they went and built a shack from what they could find, in a region that wouldn’t be known as Kakadu National Park for another two decades.

The first year was hard as John and his wife Pauline sought to build a meatworks and a better home to live in; with little in the way of funds, John would leave for weeks on end to hunt crocodiles for their valuable skins. Sab was born in 1960, and a homestead followed in 1961. Slowly, from scratch, operations took shape on the 1000-square-kilometre Munmalary Station.

The station employed Aboriginal workers from as far afield as Arnhem Land, east from Munmalary’s location near the South Alligator River.

As a kid Sab spoke the local dialect, and friendships formed over the years with local clans led to his father becoming the first person to run day tours into Arnhem Land. Sab, who bought his father’s company from him a decade later in 1999, continues this tradition today; access is restricted to a select few tour operators.

Day three: Arnhem Land

We cross the East Alligator River by driving right through it. It’s a tidal river, and if you don’t time it right you could be waiting for up to two hours at Cahill’s Crossing for it to become passable. Then we’re in, and the land opens up to us. Mysterious, beautiful and sparsely populated, Arnhem Land occupies a large proportion of the Top End and is bigger than a lot of countries.

The traditional culture that has thrived here for tens of thousands of years remains largely intact today. We drive for 15 kilometres past vivid green spike grass framed by the majestic sandstone hulk of the Arnhem Land escarpment, and splash through paint-like red puddles on the road; it’s only just May and these floodplains are covered by water from December to April each year.

We arrive at Gunbalanya, a large Indigenous community (originally established as a mission known as Oenpelli in the 1920s), and head to Injalak Arts and Craft Centre, where contemporary Kunwinjku artists produce and sell work inspired by ancient Dreamtime stories and the rock art on nearby Injalak Hill.

A sacred site of sandstone, stories and thousands of ochre paintings, Injalak Hill is one of the most significant rock art sites in the country and perhaps also one of its most under the radar; today we have it to ourselves. Kunwinjku artist Tony Nodjalaburnburn leads the way and we scramble over rocks and squeeze down narrow crevices to uncover some of the hill’s numerous rock art shelters.

I lie down on a cool slab and look straight up, tracing the fine lines of the paintings just a breath away: the styles that come out of Arnhem Land are more graphic, for comparison, than the dot paintings out of the Central and Western desert.

Rarrk (crosshatching) designs and x-ray paintings are typical of the region, and here on Injalak Hill they have been built up in layers over thousands of years, with the most recent examples just 100 years old.

From barramundi to crocodiles and kangaroos, they depict local fauna as well as spirits and the creation mother known as Yingana or Warramurruggunddji. It’s astonishing to see, but somehow what transports me the most are the small wells in the rock, round and smooth from thousands of years of people mixing paint.

We wind up and around the hill with Tony, while Sab has taken a shortcut to prepare lunch. We meet him at a rock ledge that looks out across the extraordinary expanse of the floodplains. The wide-angle view is all green, blue and red and shimmering with heat and smoke from controlled burns; there’s nothing else to do but take it all in.

After two nights at Sab’s solar-powered bush camp, we set off to the edge of Kakadu for our final overnight stop. There are no signposts for Bamurru Plains; its whereabouts exactly is gleaned on a need-to-know basis. To get there we drive through Melaleuca Station, now owned by Paspaley but originally by Rod Ansell, the blond-haired buffalo catcher credited as the inspiration behind Mick Dundee, in the film that shot Kakadu into the international spotlight in the ’80s.

Luxury safari lodge Bamurru Plains is set on Swim Creek Station, the biggest buffalo station in the country and owned by pastoralist Alan Fisher – one of the last cattlemen and bull-catchers of the NT, says Sab, and a man who doesn’t believe in holidays, which is ironic. With a Wild Bush Luxury concept and a rustic-chic aesthetic, Bamurru Plains is made up of 10 individual stilted safari bungalows and a main lodge built into savannah bush fringing the Mary River wetlands.

All sorts of wildlife call this spot home, and among our neighbours for the next 24 hours are agile wallabies, wild pigs, brumbies and even the odd white-socked wild Indonesian cow.

We arrive in time for a sundowner on the lodge’s deck as the buffalo come in from the floodplains for the night. Dinner is an intimate and communal long-table affair, where conversation with fellow guests blossoms naturally over a local-ingredient-laced menu and wine from the open bar. Magpie geese – for whom Bamurru Plains is named – provide a rowdy alarm clock the next morning, while mesh walls and the orange glow of dawn bring the chance to see the landscape come to life from the organic-linened comfort of bed. Soon it’s time to venture right into it.

Day four: Bamurru Plains

One of the absolute highlights of a stay here is an airboat ride through the floodplains, an idea imported from the Florida Everglades that sees passengers propelled along the top of the water by a giant fan, essentially, instead of a motor.

With Sab as captain, I clamber in and don earmuffs to protect from the mechanical roar. The feeling of careening through the wetlands among the birds and the buffalo is nothing short of euphoric.

From the white-necked herons, pygmy geese and cormorants to the crocs in the shallows, every creature seems complicit in a work of sublime choreography. Plumed whistling ducks lift in swathes out of the spike rush and indifferent buffalo bathe belly-deep in the water, egrets on their backs picking off flies. The timbre changes when we arrive at the fringes of a submerged melaleuca forest.

This is Kingfisher Cafe, so-called colloquially for all the kingfishers that frequent it, and it’s open for business. We edge our way in and slow to a stop. Trees lean in to form canopies, dappled sunlight plays on the tea tree-stained water and roots curl up out of the depths for breath.

The distinct woodland sound of a peaceful dove rings out – how appropriate. We stay here between the drowned paperbarks and blue water lilies for as long as we can before reluctantly heading back. As we approach dry land, Sab stalls our return by doing more freewheeling laps.

I don’t think he wants it to end either.

Getting there

Qantas and Virgin Australia fly direct to Darwin from several Australian cities. Kakadu National Park is a three-hour drive from Darwin; your guide will collect you from your accommodation.

Touring there

Operating in the dry season (May to October), Lords Kakadu & Arnhem Land Safaris creates bespoke tours for private groups. Suggested itineraries include a one-day Kakadu tour, a four-day Ultimate Peek and a five-day Top End Luxury Safari Experience.

Lords Kakadu & Arnhem Land Safaris is a founding member of Australian Wildlife Journeys, a group of expert independently owned and operated wildlife tourism operators in all corners of the country, who have joined together to raise awareness of Australia as a world-class destination for authentic and sustainable encounters with wildlife in the wild.

Visit our Northern Territory hub for more NT travel inspiration.