Uluṟu is more than a place. It’s a vessel of stories, a home and a wellspring of spirituality for its Traditional Owners. A journey to Australia’s spiritual heart with Aṉangu guides promises to reframe your sense of perspective.

Pitjantjatjara artist Charmaine Kulitja sits cross-legged on the ground, tracing symbols in the warm desert sand with her finger. She etches a small circle into the paprika-orange earth, then draws two larger rings around it. “Ngura," she says.

“Ngura means place, home or Country," explains Michelle Fuentes, Charmaine’s Pitjantjatjara-speaking translator. “It’s symbolised by these concentric circles, which can represent a campsite, a waterhole or a significant site in Aṉangu art."

Uluṟu rises ahead of us – an ancient monolith forged by seismic forces that sent it twisting through the earth millions of years ago, like a giant stirring in its sleep. The outline of the rock is unmistakable, yet I feel strangely lost.

Not because I don’t know where I am – I do. But because on Aṉangu Country, place – ngura – is many things. It is a chapter in a songline. It is a spiritual realm. It is a living vessel that holds more than 30,000 years of human experience.

In the 1970s, the eminent Chinese-born geographer Yi-Fu Tuan pioneered the field of human geography. In his trailblazing book Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, he explored how place takes on many dimensions when viewed through a human lens, rather than the framework of absolutist measurements – coordinates, kilometres and the like – so intrinsic in the Western perspective.

In this vast, enigmatic desert, Tuan’s ideas come to life. This is an expanse, I’m beginning to understand, that cannot be mapped by a cartographer’s tools. To navigate the red, beating heart of Australia, one must learn to look, listen and feel the Country, and hear the stories of the landscape from the Aṉangu Traditional Owners. Charmaine waves her hand over the impressions in the sand, and the circles disappear.

Take a Maruku Arts’ cultural walking tour

A yawning cave at the base of Uluṟu offers a shady respite from the desert’s full-bellied heat. Charmaine is pointing out the different Aṉangu symbols painted on the wall in an earthy spectrum of ochres, yellows and whites.

There are honey ants, witchetty grubs, emu tracks, and more concentric circles – ngura – some with so many rings that they look like ripples emanating across the rock face. “The more rings, the more important the site they represent," Michelle explains.

Charmaine is leading Maruku Arts’ cultural walking tour of Uluṟu. We follow her along the towering walls, remarkably curved and sculptural like a billowing ream of red chiffon frozen in motion. At one point, she pauses, beckoning us closer. “Do you see that part of the rock? Shaped like a snake’s head?" she asks, pointing up at a protruding form in Uluṟu.

In Pitjantjatjara, Charmaine begins to recount the Kuniya story – an Aṉangu Creation story about a Kuniya (python) woman’s deadly battle with a venomous Liru (king brown snake). “The rock above us is the slain head of the Liru," she gestures. “And the spirit of Kuniya herself lives on in the waterhole just up ahead."

Charmaine is sharing Tjukurpa – a system of Aṉangu belief that encompasses Creation stories, philosophy, religion and forms the basis of all life. It connects Aṉangu to the landscape and weaves together the past, present and future.

Listening to Charmaine speak is like slipping on a pair of goggles; her words illuminating the spiritual world of the Aṉangu alive in the Country, otherwise imperceptible to me. I look up again at Uluṟu. I can see the shape of the Liru etched in it more clearly now – the outline of the head, a crack in the rock for the closed eye, a boulder forming the nose.

A wallaby’s hop down the trail, Mutitjulu Waterhole is completely still, save for the sunlight splintering across the water like static on a television. “When Kuniya died, her spirit transformed into a wanapi (water snake) and came here," Charmaine explains through Michelle.

In Space and Place, Yi-Fu Tuan explored the distinction between objective space (physical and measurable) and narrative space (created through stories, meaning and worldview).

Hearing the Tjukurpa stories imbued in the landscape is a key that opens a door to another, intangible spatial plane; one that’s so magnetic it sends the needle of my internal compass spinning.

The majestic shape of Uluṟu mirrors on the water’s surface, as if to hint at the adjoining world of Tjukurpa that surrounds us at all times. The spinifex and the desert she-oaks bristle in the breeze. A black kite circles above us, as if it’s drawing the symbol for ngura in the sky.

See the stars at Tali Wiṟu

“Who knows how to find true south?" astronomy guide and Tjapukai man (from North Queensland) Michael Courtney asks. He’s just a silhouette, barely visible in the dim light of this remote, dune-top restaurant.

Tonight, a glittering sandstorm is sprawled across the sky, as it is most nights in the outback. Nobody can answer, so Michael directs his laser pointer up to the Southern Cross, triangulates with Alpha Centauri, and draws a sweeping axis across to the south celestial pole.

This is Tali Wiṟu – an outback dining experience that plates up the very best of Australian produce with an innovative, desert bush tucker spin. I sample a few ingredients from a piti (carved wooden bowl) piled high with native ingredients.

Finger limes burst with zesty beads of citrus caviar. Garnet-coloured bush plums deliver a sweet-and-sour shockwave to the palate. Leaves of saltbush are umami-rich and saline, as if they’re coated in the sweat of the Earth. All these flavours make a delicious cameo alongside mains – reduced into sauces, infused in oils and arranged as garnishes that add a delightful desert spin to the food. But it’s the star talk that’s the most anticipated course of the night.

In the vast, unbroken expanse of the desert, we learn, the stars serve as important celestial markers of not only direction, but time, too. “See that patch of dark cloud there?" Michael asks, circling his laser around a black smudge across the Milky Way. “That’s the dark emu, a constellation well-known to the Aṉangu and many other Indigenous groups. When it’s visible directly overhead after sunset, that means it’s the time of year to collect emu eggs."

I follow the laser tracing the outline of the emu suspended in the negative space between galaxies. Here, the sky is not just a celestial compass, but a calendar that charts the seasons and life cycles of the Earth.

“And over here are the Seven Sisters," Michael continues, tracing his laser across to the Pleiades. “In Tjukurpa, these stars are sisters being pursued by a man. He wants to marry one of them, but he’s from a different kinship group, so they’re fleeing from him across the sky."

In Space and Place Yi-Fu Tuan famously wrote: “Space is freedom; place is security." Essentially, space is the unknown, and place is the familiar and lived-in. In Tuan’s view, space becomes place when we experience it. Here, it seems the sky is a place of its own, just as much as the landscape around us. Tonight, I’ve glimpsed how more than 30,000 years of lived experience has transformed the sky into a calendar, a compass and a vessel of Tjukurpa stories. I’ve seen how what seems so immense and unknowable can become understood; how space can transform into place.

Journey into Patji land

“Stop the car!" Aṉangu Elder and senior Custodian Sammy Wilson signals for our 4WD to halt in the red dirt. The group, on SEIT’s guided tour of Patji, piles out of the vehicle, curious to see what’s caught his attention.

“Look!" Sammy says, pointing to the dirt road. We scan the surroundings in confusion. There’s nothing but sand and spinifex and the trill of cicadas pervading the heavy, desert air.

“Right there! On the ground." A few metres away, a thorny devil lizard basks on the road. Sammy walks over, scoops the lizard up and places it on his shoulder with a chuckle. The creature is calm and unbothered as Sammy pats its spiny skin, which looks as if it’s made of stiff meringue peaks piped all over its small body.

Sammy’s eyes are finely attuned on this parcel of land known as Patji – it’s his homeland and the homeland of the Uluṟu family. Sammy (also known as Tjama Uluṟu) is the grandson of Paddy Uluṟu, the Traditional Custodian here and a key figure in the Aboriginal land rights movement.

This is restricted land; only Aṉangu and permit holders can enter. But when our 4WD pulls up to a ‘NO ACCESS’ sign, Sammy turns to us with a grin. “Today, I am the permit," he says, as we drive on through the red dust and into his Country.

As we drive further into Patji, watching Uluṟu fade to the size of a stone, Sammy recounts the Mala story – one of the key Tjukurpa stories connected to Uluṟu. It’s a story of the Mala (Rufous hare-wallaby) people, interrupted one night during their ceremony by Kurpany, a giant devil dog.

“They went south to escape the evil thing," Sammy explains. The story, part of a songline, is only one piece of a larger chronicle. To learn the rest, you must go to the next place in the songline and learn it there. “Just like a book," Sammy says. If the land is a book, then we’re standing in a chapter. And listening to the Traditional Owners is the way to read it.

We stop intermittently to examine flora and fauna. Sammy shows us Mulga trees (where honey ants, a common bush tucker ingredient, make their nests), spearwood trees (used for fashioning hunting tools) and desert bloodwoods that weep with crimson sap (used as antiseptic).

He shows us bushfoods, plucking fragrant strands of bush lemongrass and marble-sized bush tomatoes from the land. “You have to be careful with these," Sammy says. “There are many species of bush tomato, but a lot of them are poisonous."

“But how do you know which is which?" someone asks. “I just know," he replies with a shrug.

When the sleek, golden forms of two wild dingoes pad across the sand in the near-distance, I bristle. But Sammy just smiles. “I like dingoes," he muses. “When I was a little boy, I was friends with a dingo. We used to run around together."

Through Sammy’s eyes, the landscape shifts. What once seemed like a vast, open plain reveals itself as a book, a kitchen and a medicine cabinet. And as we sit beneath desert she-oaks in the heat of the afternoon, I learn that it’s a deeply layered archive of personal history, too.

Sammy shares stories of his family; passing around black-and-white photos of his relatives, some pictures nearly a century old. Some of the history is tragic, like the 1934 shooting of Paddy Uluṟu’s brother Yokununna by a police constable.

But there is hope, too: Paddy and the Uluṟu family’s fight for land rights, and the campaign for the return of Yokununna’s remains. In 2022, nearly 90 years after the shooting, Yokununna was finally repatriated and buried. “Aṉangu are learning to fight for their land," Sammy says. “But we have to work together."

Paint the Red Centre with Aṉangu guides

All afternoon, I watch Uluṟu shift colours like a giant mood ring from my accommodation at luxury desert lodge Longitude 131°. From the bed of my safari-style tent, from my balcony, from the plunge pool – the view is magnetic and ever-changing.

The lodge’s name is a nod to its shared longitude with Uluṟu: the one-hundred-and-thirty-first meridian east of Greenwich, London. Yet, as I gaze out at the desert landscape, it’s not the coordinates that ground me. It’s the stories shared by Charmaine, Sammy and Michael. Here, I feel as though I’m at longitude zero: the prime meridian, the origin point, the only frame of reference that matters.

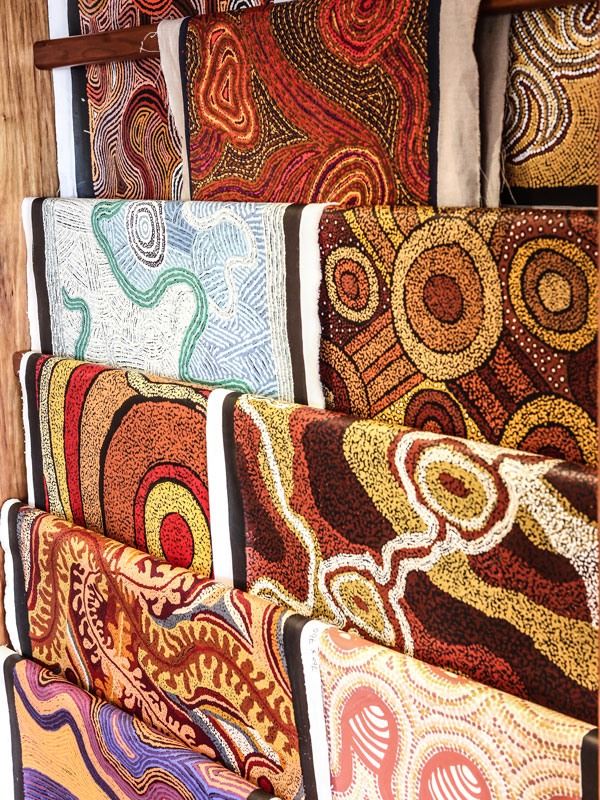

Longitude 131° (part of Baillie Lodges and a Luxury Lodge of Australia ) is an oasis in the desert, with an open bar, fine dining and walls adorned with Aṉangu paintings. I consider buying one to take home, but then I remember: I already have one; I had painted it myself with Charmaine and Michelle after our walking tour of Uluṟu.

“Have a go at painting these Aṉangu symbols," Michelle had said, handing us a reference sheet of symbols we’d seen that day. “None of these are sacred, so you’re welcome to use them to tell your own story."

Charmaine started a small fire on the sand and began working on an artwork, her hand tapping away with practised precision, creating intricate dots and symbols in a spectrum of sky blues. I asked her what she was painting. “Going out in the bush with my family. My grandmother taking me to the dunes to teach me how to search for lizard eggs."

We fell silent, the only sounds the rhythmic tapping of brushes and the crackle of fire. Inspired, I began painting the concentric rings of a ngura symbol using a deep, earthy red, to represent my time in this special place. Remembering Michelle and Charmaine’s words about the number of circles representing the significance of the place, my rings grew larger and larger, until there was no more canvas left.

A traveller’s checklist

Getting there

You can fly directly to Uluṟu from Sydney/Warrane, Melbourne/Naarm, Brisbane/Meanjin and Cairns/Gimuy. Alice Springs/Mparntwe is the next-closest airport, a five-hour drive away.

Staying there

Ultra-exclusive Longitude 131° has 15 luxury tents and one extra luxe two-bedroom Dune Pavilion. Fine dining, alcohol, activities and airport transfers are included. Sails in the Desert is conveniently located and well-appointed, with rooms and family suites available.

Playing there

On a cave art tour with Maruku Arts, you’ll learn Aṉangu symbols and Tjurkurpa stories with a Traditional Owner. Dine under the stars at Tali Wiṟu. And visit Patji homelands, guided by a member of the Uluṟu family with SEIT. It’s also worth timing your visit with Parrtjima – A Festival in Light in Alice Springs/Mparntwe, celebrating 10 years in 2025.